Maintenance Ends Press · Rick Intro

Midnight’s cats

By Stefene Russell From 47 Incantatory Essays On New Year’s Day, a day I spent stuffing straw into a Styrofoam cooler to shelter a feral cat, a man died in a Dumpster three blocks from my house. He died in the Dumpster behind the old Falstaff Brewery Apartments. People knew about it in England because it was reported on the BBC. America has already seen its first cold-related fatality of the year, as a homeless man in St. Louis has frozen to death in a bin. He thought getting out of the wind would help. Tat the insulating power of plastic trash bags would help. He was 53. Right before Christmas, a man froze to death downtown in a Port-o-Potty. He lived in it, after the city shut down New Life Evangelistic Center and opened a shelter in the old Biddle Market with 98 beds. When people couldn’t get in they just walked around all night. The night time temperature in St. Louis between December 2017 and January 2018 hovered around minus 6 degrees. The police removed his belongings: shoes, umbrella, bottle of orange juice, empty beer can, jacket, $25 Panera gift card, plastic spoon, and a debit card bearing the name Grover Perry. He was 56 years old. At the foot of the Port-o-Potty, some- one left a poinsettia, the kind you get at the drugstore with petals edged in red glitter. On every block in my neighbor- hood, three or four orange cats shelter under cars, or in empty buildings. My neighbor M. calls the empty house on Knapp the cat factory. Terry Midnight squatted in a little building on the other side of Florissant and every day fed orange cats, more than 20. They still don’t know who shot him but the day he died his daughter came and spray- painted RIP DAD/SHINE BRIGHT on the front of the building and leaned on the building and wept. Every day, people came and added something. Midnight’s photo in a silver frame. Silver balloons tied to the railing, sunflowers in juice jars, grocery store roses, candles. People sat in chairs in front of the building for hours in the cold. If I were mayor, I’d make sure every bullet was made out of rare silver and cost $10,000. The grief became a silver music and rose like notes. It rose like notes made from smoke and silver roses and glittering light, a hymn for Terry Midnight. J. feeds Midnight’s cats and P. feeds Midnight’s cats and the guy who drives the mobile dental clinic feeds Midnight’s cats. The cats have so much food the raccoons come out at night and eat the leftovers. An address is just an address, how does it magically make you a human being? My neighbor who sees ghosts said the dead don’t go anywhere. Right now there’s a lady here named Fran who grew sweet potatoes in her garden, she said. An older guy with a limp, he says his name is George, she said. He’s friendly, he says he’s a protector. So many ghosts, she said. They’re sad about the falling-down buildings and they’re sad about us falling down too. The dead grieve, she said, just like the living. A whole choir of mourners, visible and invisible, heartbroken together.

It gets late early out here

By Rick Harsch

Laboring at…laboring out…an introduction to what is necessarily to be written in diary form, scheming, strategizing—how to present the background without boring the shit out of the reader—weeks are passing and a late, cruel Mediterranean winter onslaught has yielded to the inevitable early spring of even this northernmost Medterrain, and that means vis a vis this here, that before long the boys I intend to chronicle through their baseball year will be practicing outside, maybe as soon as tomorrow (I am expecting notice to that effect). I have no choice but to introduce as I proceed, so in that vein, in the spirit of this belated if obvious awakening, let me say before continuing in re continental baseball that while I am six feet two inches tall, or about 188 centimeters, Arjun, now 14 years old, is closing in rapidly, about 5’ 9”, and his hands are already larger than mine. We checked it last night. I knew his hands had finally grown to match mine but could not recall if they had gone on to leave mine short. They have. A monkey could bite off a length—as a chimp once munched one of Jane Goodall’s digits—and he would still have the edge…so to speak. I have small hands relative to my height, while my wife has good long fingers, Indian fingers, south Indian fingers, the kind that when long and slender one imagines to be classic, long, slender Indian fingers, even if there is every likelihood that the Tamil on average has precisely the same hand size as the Scotch-Irish-Danish-English-German-French mix of Arjun’s father’s people. Maybe that’s got something to do with the movement he has for several years been able to get on his pitches, which are finally beginning to combine that movement with a speed that, should chronic inaccuracy not scotch the whole works, may elevate him to the elite among his mound-climbing peers.

What happened in regard to continental baseball is that having moved to Slovenia, leaving the United States behind, positioning myself on the Slavic side of Europe yet where my wife would gain climatically by proximity to the Adriatic, having been long in the US Midwest, I was approached by students at the university where I taught in Portorož, Slovenia, two of them on separate occasions, and neither actual students of mine, and asked if I might want to manage their baseball team. It’s just like baseball to come calling when least expected (leaving the US I didn’t give the loss of baseball a thought; but I should have, for I was soon closeted in an English department with a Twins fan, something I would wish on no one I felt neutral or better towards). Having long been a fan, having managed here and there—the high point being a group of foreigners at a university who never actually played a game; the low point steering a group of softballing women who were damn serious about results in a Kenosha working league—I answered in the affirmative when the second to approach actually gave a date and place, before even giving the matter the least thought…with the result that when I showed up in the nearby Slovene port city of Koper on the gravel lot that was to be ours for the next several years and was handed the reigns, I had to improvise, that is to say coax an appearance of leadership quality to my projected surface. I still remember the striding along the sidelines as they played catch, noting that Martin Mavrič, who had finalized the deal, had a relatively good arm, throwing the ball more or less like a real baseball player.

But what was next? We practiced. I no doubt hit grounders and fly balls. I could still pitch, even throw a curve, if slowly enough the best tennis player among them could wait on it, calculate the movement, and, being a lefty, guide it along the third base line, which is where the grass was high, where the balls disappeared, where the nutria moved freely as there was a canal nearby. Just ask Simon, the manager who took my place at the end of the year after I resigned. He hated losing balls so much he refused to sanction batting practice. (I saw his ex-wife today, incidentally, and his son, who recognized me, the genial little winner of fading hearts, Aleksander.) I tried to make as many practices as possible during those years, for as a coach I could still make decisions when Simon wasn’t around and the players found the batting sessions so liberating the righties pulled just about everything, which meant into the nutria brush and though we were never entirely out of balls, we seldom finished a practice with more than a few left.

So we practiced, yes, but for what? For games. There would be games. So there must be a league of sorts. Yes, yes, in fact, the leagues were common to most European nations, and Slovenia was included. Before that year they had four teams, three in Ljubljana and one in Škofija loka (pop. 11,800), the Foxes of Kranj (pop. 37,373) or Kranjski Lisjaki, for some reason not the Škofija loka anything. Probably the majority of players were from the larger Kranj, but had no field, while Škofija loka had the field and no players and so the argument regarding the name was one-sided—to my ultimate benefit, for to this day I enjoy rather overmuch saying aloud The Foxes of Kranj. I know of one large and unpleasant man who seems to actually be diminished by my saying it with a near British deliberation—he played first base for them back then.

Not having a field in town is no laughing matter. Our team was new, joining the league along with a team from the town of Novo mesto (pop. 23,000), which didn’t, for some reason, give themselves a nickname, joining the Ljubljana teams of Golovec and Ježice as essentially nameless teams. We were, being coastal, The Swordfish, Mečarice, and I have no doubt the founding players of Mečarice imagined getting a field somewhere in the reclaimed land in the port region—Koper, formerly the Italian Capodistria (Koper means dill, so it is as prosaic in comparison to its historical name is you might guess), which was an island that became attached to land, and then more land as it needed to accommodate the port of a nation, first one of many ports of Yugoslavia (which once considered building an airport here and constructing a port where there are now historic tourist attracting salt pans adjacent to the Croatian border, even mixing with the Croatian border as they are in a bay that is split between the two nations), and now the only port of a nation with a coastline approximately 47 kilometers long. The old city is now ringed by new constructions and vast acreages of nutria teeming, canal-crossed fields, many of them converted into outdoor sporting facilities. Back in the summer of 2003 it was easy to imagine spending a year or two practicing on our gravel parking lot for a couple years before a humble baseball stadium was provided us. Alas, it never happened, and after some time the Mečarice were extinct.

But not before some grand efforts to prove we belonged in the Slovene major leagues. Indelible is our 39 to 1 loss to Jezice, along with several other lopsided scores from that year, which yet included a victory, over Novo mesto: Mečarice 40, Novo mesto 4. I pitched in that game. I was a legend of a kind, the American guy, asked before that Novo mesto game by one of their players if I had really played in the Major Leagues. Not really, I replied, leaving a great deal of leeway open for interpretation. I pitched a solid inning, my last ever in competition, giving up one hit, one unearned run, striking out one and walking one. I played part-time. I was about 43 years old on a team that averaged perhaps 23 years of age, a team of several great athletes, none of whom had played competitive organized baseball before that season. Ljubljana, on the other hand, actually had little league, highly organized, and their adult teams had on the roster players who had been at it most of their lives. The Foxes of Kranj even had Jesus, formerly a professional at some level in the New World. I benched myself when he pitched. I was never not a legend, but the meaning of that is in my assertion of self as manager from a land that knows baseball rather than as a player of any worth. It became clear to me early on that when it came to the society of players, coaches, managers and umpires, the Slovenes had it all wrong. The umpires were tyrannical, rather like airport security guards, nearly apart from the game itself, a bit like severe robots. They also tended not to be expertly versed in the rules of the game and, this is already evident, they lacked common sense. Nobody argued with them and this simply would not do. I was asked, as a man from the land of baseball, to manage a fledgling team, to introduce this team as it were, to the world of organized baseball—and that simply would not have been possible without teaching my players and any opposing players and their staffs, even the umpires themselves, that in the game of baseball the umpire is the enemy of mankind and if you think he’s wrong he more than likely is, and if you think that you must needs get the point across to him…Else injustice reigns.

I’ve published an account of this process and its delights elsewhere (Chapter 13: The Inherent Human Transgression That Is Umpiring: A Slovene Case Study, in ANATOMY OF BASEBALL, SMU press, 2008, ed. Lee Gutkind, forward by Yogi fucking Berra!) so I’ll get on with what matters regarding my son and his baseball career and the phenomenon of Italian little league baseball. We never got ourselves a field, but some enterprising member of the team managed to get us a home field one year up in Villa Opicina, Italy, which is where at the aforementioned karstal grounds I played my last competitive ball at the age of about 48, batting precisely .400, 4 for 10, one of those four being a double that remains in my physical memory reservoir and will until on my deathbed I bedevil the hospice nurses with the event, a pitch lower than my waste on the outside part of the plate, let’s call it a curve, that I met with full speed of wrist and coordinated arm action, absorbing that nonpareil feeling older men get when they realize they are going to make it somewhere they don’t often arrive to, in this case second base on the trot. One of those ten hits was a hard grounder to third that Simon judged an error and I altered in the scorebook to read single, as I believe it fell in that category of indefinite that because the god of baseball is good awards the more positive result all the way around. The batter gets a hit, the fielder is not charged with an error, and if the pitcher is indeed punished with the mark of baseball Cain for the hit, he is at least assured the runner will not advance home if the next batter does not put the ball out of the park. Mercifully, the season ended in a benign definitive fashion. We were going up against the latest new team, Maribor (pop. 95,000, no nick-name), upstarts truly, but they had us by a run when I came to bat with two runners in scoring position and two outs in the last inning, a mere teenager on the mound. Perhaps a ball taken, a foul ball, who knows: what is quite true is that before long I saw a pitch I could surely drive, and did drive—I mean, I really connected—and I lowered my head gamely, for if running all the way to second was the thing to do I was going to find a way…yes, I lowered my head and as I was rounding first saw Maribor celebrating…what to me was a ball ripped to left center was described to my face later with no little mockery as a bit of a lofted liner-type, wounded bird flighty ball the shortstop did not even have to back up for to catch easily.

Timber

By Bell Roe

Before her “breakdown,” my mother would rip up the countryside with girlfriends half her age… plague area drive-thrus with unreasonable Happy Meal requests; cruise back roads half-seeking, half-fleeing the monsters raised by those “value-added” famers (the sudden apparition of a llama prompted screams of dread and delight, the flash of an ostrich…don’t ask).

These young women enjoyed my mom’s family stories and her way with a catch phrase. “Did you seen me, Lippert?” and “Hands up, Pickle!” embroidered into conversation with brilliant ease.

One girlfriend tried to set my mom up with her father, a farmer who lived up in the northern part of the state. I don’t think my mom suspected, or she never would have allowed herself to be placed in such a situation.

Upon their arrival, the gentleman, dressed in crisp overalls, showed my mother to a hay rack with bales of hay wrapped in silk. Once ensconced, she was driven into the woods to a pond, where he plunged his arm underwater to produce an ice-cold six-pack of beer. My mom fled to the house where her friend was waiting hopefully.

After a fitful night of sleep in an upper room of the farmhouse, my mother declined an invitation to accompany the man and his daughter to church. He must have thought this woman one strange fish to resist both his incredibly tender courting and God.

But this has how she has always been, from her days as a young beauty sniffing at wall paper samples to her nights now as a wizened senior sipping chocolate milk from a jug.

The downstairs of the house I grew up in was remodeled in an effort by my father to save his marriage. The pine pocket doors and trim were ripped out to make way for a sliding glass door that opened onto a five-foot drop. A Mt. Rushmore-looking fireplace saw a few smoldering sticks before it was closed up for good.

My mom grew up farmer royalty outside the town of Norway. A tiny town named after a full country should be a good sign of wild hopes if not hubris, and my mother’s family claimed the blackest dirt upon their flight from Bavaria with a rumored haul of gold.

To hear my mother tell it, her childhood on this farm was mix of mist and myth, set on the verge of an old-growth forest they referred to, in hushes, as “The Timber.”

There were the stories of aunts who darkened their hair with black walnut hulls and the hours she hovered over her own mother in a sewing room at the top of the house painstakingly separating the gray hairs from black.

Further back, when she was little, my mother would meet her girlfriends in the timber. They would gather in the northeast corner, converging from their respective directions and farms: the clique of sisters from the family to the north who raised Gloucestershire Old Spots, also known as lard hogs; only-children from the clay-tinged soil to the south, doomed to lives as spinsters or nuns. Once the group was gathered, my mom would take the helm. She remembers having had each girl bring something: a flower, a fern, an arrowhead. She doesn’t remember what they did with these things. I wondered if each child was gently commanded to make some sort of report from the center. She said she didn’t remember much of what else took place. “Did you play out stories, make up characters?” I asked. No, she did not think they did.

The day of the big party came and everyone had a blast. I remember it well. The yard was full of cousins, aunts and uncles. Watermelons were split. It went later than any family party before. I remember hearing the reassuring sound of voices in the hay mow; the lights were on in the attic.

This memory had come to her as we started north (from our former movement west) on one of our excursions, usually toward the promise of the brief incandescence that live music brings.

“Doesn’t north feel different?” she asked.

“How?” I asked.

“It feels like going up.”

“So south feels like down,” I said, naturally.

“No, south is a feeling of comfort. East is clear, and west is…jumbled.”

My siblings and I were white-hot envious of our cousins who grew up on the south side of the timber. They built exquisite forts, caught crawdaddies and essentially “ran away from home” every time they stepped off the back stoop. They were wilder, from the look in their eyes to the way their fingertips burned our skin when they touched us “it” or pulled us from our early graves of potato sacks and salamanders during hide-and-seek.

This envy has never worn off and I suppose that is the root of my own disrespect for order, the reason I headed in the jumbled, mixed-up direction when I had the chance. I realize now this was all in relation to those woods and my outlaw mom, her secret regimens of metoprolol and pine cones, her requests for odd luxuries like her childhood tributes of arrowheads and ferns.

She stays in bed now nearly 24-7 watching satellite TV. She is equipped for and capable of doing nearly anything or going anywhere, yet she chooses to stay locked in what she refers, in hushes, to as her “dungeon.”

“What’s there to do? Where’s there to go,” she moans, poster child for a depression that is still all disappointment.

I remember the time our farm played host to one of the annual family parties. We didn’t have a timber, not even a grove. Partly to remedy our embarrassment, I think, I proposed to my brother that we come up with a “haunted house” to run guests through. We worked for weeks, cooking various types and brands of pasta, for various durations, to come up with the best bucket possible of guts and brains. We transformed a downstairs closet into a horror chamber where guests could be poked with long twigs of broom straw and prodded with vacuum cleaner attachments.

The day of the big party came and everyone had a blast. The yard was full of cousins, aunts and uncles. Watermelons were split.

It went later than any family party before. I remember hearing the reassuring sound of voices in the hay mow, the lights on in the attic, shining out like a beacon.

It was such a success that my mother and father forgot all about their promise to talk up the haunted house part of the party and corral party-goers onto the porch where we waited in vain by the “portal,” which we’d crafted from a refrigerator box and rusty chicken-house hinges. We begged our parents to advertise the attraction as guests filed out. Just gloss over the fact that Halloween was months away, we said, and don’t mention they might end up spattered in ketchup. My parents told us it was too late. They were sorry, but couldn’t we just be happy that the party had gone so well?

I remember so clearly the crushing sensation of total disappointment. Because it was the first, I think it was the worst. I couldn’t believe that life could do this to someone. I remember my bottom lip trembled, literally trembled.

I’ve had worse disappointments since: romances ended, loved ones killed, dreams shattered; they were all brutal. But the haunted house was the ultimate letdown.

My mom had her Timber. The second-youngest of five, she went on to be the first in her family to attend college and procured a teaching degree from the Iowa State Teachers College in Cedar Falls. She married the guy in her class who was a dead ringer for Elvis. She remembers him showing her off at gatherings on his side of the family. Life was only getting better…

So I think now I can give my mother’s stories credit (even if they don’t add up, even if they are only distance voices from a barn or lights glimpsed in an attic) for keeping me going for that jumbled mix of the imagined, and gracefully restored.

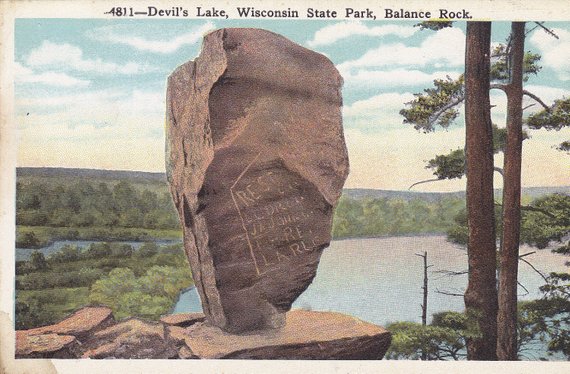

I’m pursuing the end of the world petroglyph idea and as part of a working trip to Wisconsin visited the only publicly accessible ones in the state. I had just read an essay in The Believer about young college men being drowned in some kind of smiley face cult conspiracy and then right before I came upon the glyphs there appeared a really frightening piece of smiley face graffiti. Lucky I’m too old to be caught up in the Zeitgeist!

I’m pursuing the end of the world petroglyph idea and as part of a working trip to Wisconsin visited the only publicly accessible ones in the state. I had just read an essay in The Believer about young college men being drowned in some kind of smiley face cult conspiracy and then right before I came upon the glyphs there appeared a really frightening piece of smiley face graffiti. Lucky I’m too old to be caught up in the Zeitgeist!

An Open-And-Shut Case, Johnson

By Joe Blair

Reposted from joeblairthewriter.com

Black Lives Matter. That was the theme of the sermon. And so, near the end of the church service, when Reverend Bryant is saying, “Come up to the altar. Anyone who needs a prayer,” I being white, like Darren Wilson, and the remainder of the church being black, like Michael Brown, I certainly don’t want to come up regardless of what prayer I think I might need.

Earlier in the service, Reverend Bryant broke the congregation up into four prayer circles: one group would pray for our public institutions, one would pray for our community, one would pray for our church, and one would pray for our police officers. She didn’t feel the need to justify the first three, but of the fourth she said, “If someone breaks into my house, you know I’m calling 911.” There’s more, but I’m not listening because I’m busy trying to reconstruct the Dave Chappelle stand-up bit about why black people are afraid of cops. “Sometimes we want to call them too,” he says. “Someone broke into my house once. This’d be a good time to call them. But…” he’s shaking his head. He’s not calling the cops. “My house is too nice,” he says. And he knows that the cops are going to hit him over the head for being a black man in a nice house. The officers will then look around, hands on hips, and say, “It’s an open-and-shut case, Johnson. I saw this once before when I was a rookie. Apparently, this nigger broke in and hung up pictures of his family everywhere.”

And now, “Come up to the alter,” Pastor Bryant is saying, “anyone who needs a prayer. Anyone who needs a prayer. Please come up.” It’s odd to find myself, against my will, stepping out from my pew and walking up the center aisle. I have never wanted to draw any attention to myself whatsoever.

And now, “Come up to the alter,” Pastor Bryant is saying, “anyone who needs a prayer. Anyone who needs a prayer. Please come up.” It’s odd to find myself, against my will, stepping out from my pew and walking up the center aisle. I have never wanted to draw any attention to myself whatsoever. This has always been my tack where church service is concerned. I’m from the humble Methodist tradition of quiet prayer. I have always considered making a display of my prayers disingenuous and self-serving. But now I’m at the altar.

It occurs to me, when I arrive, that standing and walking was the easy part because I’m not sure what to do now. Another person has come up as well, a woman who announces that she’s joining the church and everyone except me is shouting and clapping and I stand there, hands clasped in front of me like an altar boy. This clapping and shouting goes on for a while. I wait, alter-boy like, unsure of what to do. I’m still facing front, feeling a bit separated from reality, when the diminutive pastor Bryant appears in front of me. “Do you need a prayer?” she says.

The chapter upon which she had based her sermon was John 9. A man had a son. The man’s son was possessed by a demon. The demon threw the man’s son to the ground and made him froth at the mouth. Sometimes, the demon threw the man’s son into the fire. Sometimes into the water. The man asked Jesus to help him. Jesus told him that if he were able to believe, then all things would be possible.

“Rabi,” said the man, “I believe.” And then, in the same breath, “Help my unbelief.”

Pastor Bryant, after reading the passage, admitted to being unsure why God had led her to it. It didn’t seem to be a natural fit with the theme she wanted to prosecute.

If my son Michael lived in the days of Christ, we would say he was possessed by a demon. These days, we say he suffers from seizures. Michael doesn’t have much language. The language he does have is unreliable. When he says, “I want pizza please,” for example, he might mean, “I want to go for a ride in the car.” Yesterday, when Michael kept asking for chicken, Deb and I decided to believe that he did actually want chicken. So we drove to the Coral Ridge Mall for Panda Express. In line, Deb wondered whether we should get him a double order of the orange chicken, which is his favorite, or one order of orange chicken and one of something else. What did I think?

“I don’t know,” I said. “Mike, do you want orange chicken?”

Mike didn’t respond at all.

“Orange chicken,” I said, “or beef?”

He didn’t respond.

“Well,” I said, “we know he likes orange chicken, so let’s just go double on that.”

Mike isn’t a small kid. At sixteen, he’s six foot one; two hundred and twenty pounds. It looks a bit odd seeing my petite wife leading him around by the arm. We have often worried that he’d realize, one day, that he didn’t need to do what we told him.

I left Deb and Mike at the table and walked across the food court to Safari where I ordered a Gyros platter. Safari always takes a little longer than the other places and I got the Gyros to go, assuming Mike would be done with his orange chicken by the time I got back. As I approached the table, I noticed that something wasn’t right. Orange chicken and fried rice were scattered across the floor. An upside-down paper plate. An upturned paper cup. Deb appeared to have pushed herself away from the table, her arms at full length and she was laughing. Mike was sitting rigidly in his seat, expressionless. I didn’t notice the police officer. Nor do I notice that the food court had fallen silent and that the patrons had vacated the space around Deb and Mike’s table. I glanced at Deb again and noticed that what I took for laughter wasn’t laughter. She was crying.

Michael had tossed his full plate of food before he attacked his mother. He first grabbed her wrists and hands, bloodying them with his fingernails. He then took a swing at her head. Deb ducked the blow and then pushed the table into Mike’s midsection to keep him away. An officer was shouting at Michael to stop at the same time Deb was shouting, “He doesn’t understand you! He’s autistic! He doesn’t know what you’re saying!”

Michael had tossed his full plate of food before he attacked his mother. He first grabbed her wrists and hands, bloodying them with his fingernails. He then took a swing at her head. Deb ducked the blow and then pushed the table into Mike’s midsection to keep him away. An officer was shouting at Michael to stop at the same time Deb was shouting, “He doesn’t understand you! He’s autistic! He doesn’t know what you’re saying!” The officer, much smaller than my son and visibly afraid, continued shouting. “You need to stand down right away! Stand down! You can’t do that!” And then, “Don’t worry, mam, I’m calling for backup!”

“My son is sixteen,” I tell Reverent Bryant. “He can’t talk much. So, he can’t tell us what he’s thinking. And he’s getting real violent.” I pause. And then I struggle on. “He attacked my wife again. I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Reverend Bryant calls all the men of the church forward. To stand around me. “If you can’t touch brother Joe, then touch someone who is touching him,” she says. And then she, leading all my brothers and sisters in the church, says a prayer for belief.

Joe Blair is a pipefitter who lives in Coralville, Iowa, with his wife and four children. His essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Iowa Review. His critically acclaimed memoir, By the Iowa Sea, was published by Scribner in 2012.

I think of Anne Tkach

By Chris King

Originally posted April 2014 at Confluence City

I have a favorite Anne Tkach memory.

The setting: Fred Frictions’s kitchen, adjacent to Frederick’s Music Lounge in its heyday. The time: somewhere in the middle of the afterparty that never ended while Fred Jr. was running the Lounge. We were drinking, smoking, and passing the guitar, naturally. I know Roy Kasten was there, because we locked eyes in joyous amazement when the simple chords Anne was strumming turned into a song that Roy wrote with Michael Friedman, “Everything You Love Will Be Carried Away.”

Joy and amazement: not uncommon experiences, when Anne Tkach was playing music.

The specialness of this particular musical experience requires a little explanation, since most people, unfortunately, don’t know who Michael Friedman is or the kinds of songs he writes.

Roy and I went to graduate school in literature at Washington University with Michael. He was an obsessive fan of poetry and songwriting who suddenly started writing songs, frequently with Roy’s assistance on guitar. The typical Michael Friedman song is very long, intensely personal, allusive in complex ways, and for those reasons difficult to learn and to sing.

There was a time when Roy and I were the only fans of Michael’s songs. Anne and other musicians began to hear his songs through the Guitar Circle, a song-swap that we started at Michael’s instigation when he still lived in St. Louis and wanted to encourage his little brother, who was passing through town at a tough time, to focus on his own songwriting.

Through the Guitar Circle, some of Michael’s favorite musicians and songwriters – Anne, Fred, Bob Reuter, Mark Stephens, Sunyatta, Adam Reichman, John Wendland – became fans of his songwriting. Roy drew upon this incredibly deep pool of talent when he produced two records for Michael, “Stories I Have Stolen” and “Cool of the Coming Dark.” Anne played bass on three songs on “Cool of the Coming Dark,” including “Everything You Love Will Be Carried Away.”

She played those bass lines as tastefully as can be imagined, though they were anything but hard for her (or anyone) to learn. Like many of the best singer-songwriters, Michael and Roy go in for the three-chord, two-part songs. But learning a Michael Friedman lyric poses a real challenge for anyone. “Everything You Love” has five long stanzas with absolutely no predictable rhymes or familiar lines, unless you happen to have read every book and heard every record in Michael’s extensive collections.

As Anne broke into the first verse – it’s about Bob Dylan accepting an Oscar on TV, though typically for a Michael Friedman lyric, Dylan is only alluded to, never named – sitting around Fred’s kitchen table, I could see that Roy had no idea she had been learning their song on anything other than bass. It is, needless to say, the highest tribute a musician can pay to a songwriter, to learn one of their songs. Anne was a musician we admired as much as any musician in town, on Earth. It was an unforgettable tribute.

Anne eventually recorded her version of their song with her band Rough Shop on their record “Far Past the Outskirts,” which I only heard after I learned that Anne had died in a house fire. Anne played in a lot of bands, a lot of really great bands, and they released a lot of records, a lot of really great records. When I started sorting through my collection for records Anne played on, to deal with my grief, I found about 10, and I’m sure that’s less than half of her recorded output. Even these 10 records – with the bands Nadine, Bad Folk, Peck of Dirt, Michael Friedman, Ransom Note, Rough Shop and Magic City – would make for a musical career that would make anyone proud.

And that is even with a career, with a life, cut tragically short, when Anne was at the height of her creative powers as a musician and just starting to emerge fully as a songwriter and a singer. I am in awe at her accomplishment, and unspeakably saddened at her sudden loss.

I have a few more personal thoughts about Anne.

She was an incredibly supportive friend. Anne must have attended every event our arts organization Poetry Scores produced. I have many memories of her strolling into an event – in recent years, accompanied by the love of her life, Adam Hesed – and making an effort to connect with everyone before she moved onto the next friend’s gig. Our events are collaborative, so she could have been supporting any of a dozen friends, or all of us. Hundreds of St. Louis artists would say that Anne was there for them, again and again.

I must say she also handles a band break-up as skillfully as I can imagine that being done. She briefly played in a version of my band, Three Fried Men, after Robert Goetz invited her in on drums (another instrument she mastered). As dozens of musicians would tell you, she was a pleasure to play with, learning songs without apparent effort, knowing what to play without being told, having fun in the process. Robert and I had a falling out after only a few band rehearsals, unfortunately, and I lost Anne in the split. I don’t remember how she told me she’d rather play music with Robert than with me – my memory sparing my ego, perhaps – but I do remember it left no bad taste whatsoever. My friendship with Anne continued without a hiccup.

I am very relieved to say Robert and I later patched things up, and he was the next person, after Roy, whom I called when I heard that Anne was gone. I needed to speak to someone with whom I had shared, however briefly, the experience of playing music with the one and only, the irreplaceable and unforgettable, the immortal Anne Tkach.

Anne’s friends have been seeing a lot of each other since she died. A series of events in the local music and arts scene became tributes to Anne – wakes, in a way – in the week and weekend after we lost her. The way we lost her, in a house fire apparently sparked by a lightning strike, left us all numb and perplexed. The fact that she was sleeping in that house to care for her ill father only made the loss more deeply unjust and inexplicable. We have all been talking about that.

I was talking about that with Robin Allen, a fellow musician, at Dana Smith’s art show on Friday. Dana is also a musician whose band Cloister gigged with Anne’s bands. Everybody at the art show was grieving. I talked to Robin about how the whole lightning storm thing was making it harder for me to grasp her death and come to terms with it.

“In a way,” Robin said, “the way she died, it’s like we all got struck by lightning.”

We were also talking about that the night before, the night of the day we all heard the tragic news. We were drinking and waking Anne at Ryder’s, the bar owned by the love of her life, Adam. The same violent storm system that apparently killed Anne was still blowing through St. Louis. I was sitting near the front door with Robert Goetz, Gina Alvarez and Kevin Belford.

The storm kept blowing the door of the tavern open, and then closed again. Since the door was also being opened and closed by people coming into the tavern, it was a little weird whenever the door opened and closed, but nothing came into the tavern but a little bit of the storm.

I decided that Anne was a part of the storm now, and that Anne kept coming into the tavern, connecting with her friends, and then moving onto another friend’s gig. Whenever a lightning storm comes to St. Louis now, I will think of Anne coming to see us. Whenever I hear her music or see lightning in the St. Louis sky, I will think of Anne Tkach.

Adalwolf & Mossyback

Then there was Adalwolf. He lived up on the ridge in what was basically a cabin, on the edge of the Amana timber. He owned some of his own timber, hunted and mushroomed it. And the view was pretty good. Adalwolf could see the Wolfe place from up there, and almost all of the bachelors. This brought him under some suspicion, of course. He deflected it well. One of the more recent German immigrants to the county, he still had a bit of an accent and made a good show of not understanding fast talk, oblique talk, or dirty talk. That last one was part of a huge joke that kept on giving.

The other thing that diverted attention from Adawolf was the movie production that descended on his place in the spring of 84. Adawolf got himself installed as advisor on the flick and nearly foundered on the rich craft service. The movie was about a pioneer girl who falls in love with a German frontiersman named JOACHIM.

The Cedar Rapids Gazette was out there at least three time interviewing the cast, and then the crew and then Adawolf. Same with TV 9, 2 and even 7. The Adawolf coverage was probably the best. We had to admit. He was charming, even more than the actress who played the pioneer girl, Elsa. She got her break as one of the cousins on Anne of Green Gables and then graduated to a zombie franchise. You can imagine how Elsa’s arrival stirred up the bachelor pot.

*****

I’m not much of a party hound; that’s probably why I’m still a bachelor. There were always lots of keggers up past Adawolf’s place. It was just wilder up there, pretty wooded for a tame and scored out place like Iowa. The guys always got the girls to coil up tighter against them by mentioning Mossyback. Mossyback was our version of Big Foot. “He always waits at the edge of light,” said Jim, “the edge of any light.” Gail Becker, the party’s hostess, claimed the outside window sills of the ranch house she lived in with her sister were covered with strange pockmarks, evidence of Mossyback gnawing in frustration and sadness on the wood. That was the summer the B52s first record came out. “Dance this Mess Around” and “Rock Lobster” were played only in the party’s dying throes. The “cool” kids didn’t get those masterpieces. In fact, if it wasn’t Boston or Foreigner, it cleared the room. It wouldn’t be until college that the straggle of gay kids and weird kids staring uncomfortable at each other across the room could finally break loose from the walls they were holding up and enter the ring.

Regarding darkness and my Dad’s horse

By Lisa Hannon

Last night I discovered my parents’ neighbor had left a message regarding Dad’s horse, whom he’s feeding while they’re out of town. She’s not been doing well since Sunday, and yesterday evening he couldn’t get her up, let alone into the barn. He thought she’d probably be okay till morning. But then he just ha-a-d to say, “I don’t know what will happen if a pack of coyotes finds her.”

Well, crap. I got in the car and drove through the starry countryside to the farm. Here’s how big a chicken I am: I was in tears because I was scared of how scared I was going to be when I got there. I’d asked a couple friends to come along, and they weren’t keen on the idea, so I was going alone to do… what? Sleep on the grass beside the horse? Fight off coyotes with my bare hands? I think a lot of things are getting to me right now and I feel utterly helpless to ease the suffering in the world, like the pain my friend Dave is in while dry heaves rack his frail, cancer-eaten frame, and the suffering our upcoming war with Iraq will bring.

I pulled into the pitch-black yard and left the headlights on, pointing past the barn. The darkness was hugely silent and thick with stars, and as I found a path through the long grass to the gate, I could hear water dripping off the barn into a tall patch of nettles, and it sounded like the echo of someone hitting a baseball. Some of the weeds were over my head, and I walked down through the shadowy barnyard and out into the pasture, until the bobbing circle of flashlight picked out the buckskin stripe of a large, plump horse lying on her side. Uh oh. But then–bless her–she hove onto her feet and stood. Her backside was aimed towards me as if to kick should I come too close. I know next to nothing about horses, but this was an encouraging development. I did not think my wavering courage extended to exploring the yawning farm buildings for a rope, but I did cast my flashlight beam ‘round the barnyard to see what might be out in the open.

Eyes. There were brilliant, gleaming eyes in a tall stand of weeds across the cement yard. I strode quickly in that direction, expecting the eyes to disappear and the thing to slink away like a ‘possum or raccoon would. But they stared me down. “HAH!” I shouted, thinking to myself that I wouldn’t be scared of me, either. I made out a long, grayish form, too large to be a cat, standing silently and watching my approach. This ridiculous plastic flashlight was not going to be any use if I needed a weapon. Just then the eyes disappeared. Not a sound, not a rustle of movement in the weeks, but they were gone.

I exhaled. Somewhere in the next field, you could hear a soft squealing and grunting, just on the edge of hearing if you strained. I’d read some director of thrillers, possibly the director of “Signs,” quoted that it builds anxiety when the audience isn’t sure whether they heard something or what it might be if they had. I could personally attest to that dynamic right now. No, I don’t think seeing “Signs” would have helped me one bit.

I went into the dark house, turned on several lights and tried again to dial my dad, getting busy signal after busy signal. Finally, at 11:30 p.m., the phone rang and there was my dad’s comforting voice of optimism, telling me to go home. He didn’t think the coyotes would hurt the horse, and she should be fine until I reached his veterinarian in the morning. A part of me wishes I’d had the guts to sleep next to the horse that night, but I almost leapt at my dad’s advice. I didn’t even turn the yard light off because I couldn’t handle walking back to my car in the black of night. I felt anxious and exhausted.

As I crossed the lighted circle of gravel, a sudden loud shriek tore the stillness. “Oh, Jesus!!” I cried. This time it was clearly raccoons, squabbling in the branches above my car, trilling and squealing and making my heart shake as hard and fast as the leaves beneath them.

I drew in a breath and laughed at myself, but locked my doors as I drove away past the towering, silent corn.

Part 2

I met the veterinarian the next day, and he gave the horse a shot of vitamins and painkillers. As I write this years later, I no longer remember what he said in response to my fearful question of whether my dad’s old horse had reached the point she should be put out of her misery. I think he acknowledged she was on the downhill slide, but the injections would make her easier, and we could see how it went. Neither do I remember why I made another visit with my friend Linda, when the neighbor who’d first called lived so close and we didn’t. Maybe I’d offered to relieve him, since the easy favor he’d agreed to do had morphed into a more stressful responsibility.

Linda, whose own horse was in the prime of his life, burst into tears when she saw my dad’s elderly pet lurch to her feet and stand trembling, balanced on the edges of her hooves. Her knee-jerk reaction was to suspect my father of neglect. My tears were quieter, and the reason that Dad would probably rather I hadn’t been involved: I’m a worrywart with a tender heart, and a tendency to see things as worse than they are. No doubt it was a balancing act for him to gauge the horse’s condition through the long-distance lens of me; he also didn’t know that the neighbor was privately almost as worried as I. When I asked him if I should have the vet put her down if she was suffering, he said a loud “NO,” and was adamant that he would be the one to do it if it became necessary. He’s not usually stern with me, but this horse had been part of his life for decades. Please, God, help her, I thought, because Dad is five days out and there’s no way I can leave her suffering. But at what cost to our relationship? What if he didn’t get to say goodbye because of my decision?

Linda decided, on further reflection, that she wasn’t accustomed to older horses and the situation wasn’t as dire as it had felt, just heartbreaking to see an animal enduring pain; still, she dreamed about her that night. The vet called at 8:00 p.m. to say he’d given the horse a sedative, and she might sleep. Because I’d called the Department of Natural Resources the preceding day, and the guy who answered supposed it was possible coyotes would attack a horse if they thought she was on her last legs – which they might if a sedative had knocked her out – I headed for the farm after my desk job. Sometimes you just gotta do something because you’d kick yourself the next day if it went wrong because you hadn’t.

It was again dark as I drove down the lane, which was like a tunnel formed by the steep embankment on the left and the Autumn-high corn on the right, and turned into the barnyard. The asphalt around the old gray barn was cobbled now, season after season of Iowa frost having expanded and contracted it, so I inched along with the light from my headlights bouncing from the barn roof to the asphalt to the trees beyond the barn back to the asphalt, and then onto thick grass, where I accelerated to keep moving into the pasture. The horse was still awake, and didn’t seem to mind a vehicle pulling in beside her. The night before, it hadn’t occurred to me that I didn’t need to doze on the grass exposed: I could sleep in my car. I switched off the headlights, reclined my seat and listened to soft music on the radio for awhile, breathing the sweet smell of horse and hay until I was sleepy, then turned off the car, rolled up the window most of the way and let crickets be my lullaby.

I dreamt my ex-boyfriend realized he’d made a mistake and still wanted me. It had hurt every day without him, and I was just on the verge of kissing him when I remembered he was married now and woke with a start. It was 3:00 a.m. Darkness, softness, bright starlight registered on my awareness. I’d forgotten how you can see in the country night like it’s deeper day, or a bedroom-lit blue. The chorus of insect song was dense enough to touch. I could see the shadowy form of the horse, still upright after the shot the vet had given her. In fact, she was walking, slow and faltering, but walking all the same, and she could reach the ground now to pull grass. The soft tearing and munching sounds came closer in the darkness.

I got a pan of water from the barn, no longer afraid of shadows, and held it for her while she drank. Maybe somewhere inside me a horsewoman does sleep, because I could have stood there a long time breathing in that wonderful horse fragrance and understanding viscerally the closeness my dad felt to this large, gentle animal.

In the morning when I opened my car door, she neighed at me and it was better than the sunrise.

Lisa Hannon was born in Cedar Rapids and still calls Iowa home, even though she’s fallen in love with her adopted city of Portland. She earned her BA in English from Iowa State University, and, like many English majors, has held a variety of jobs, including bar-tending, flipping burgers, answering a switchboard and dissecting rat brains. She is a professional “hugger,” having learned from the best of them, Amma, India’s “hugging saint,” and rockstar of the Free Hugs movement, Ken Nwadike Jr. Now she combines blogging with hugging on her Facebook page, HUGS HERE Portland.

Stuck here forever, with you

By Amanda Coyne

This piece originally appeared in the first issue of Little Village magazine, July 2001

I give him a look. “OK, OK. Detroit,” he admits, “I was born in Detroit.” I decide to discontinue the questions. But he continues the answers: “And don’t forget about the time I sailed across the Pacific on a homemade boat, with two complete strangers.”

“I’ve heard this story, Gary.”

“How about the time Bob Novak sat in on the ‘Sanders Group?'”

That gets my attention. But because I want to talk about Robert Novak, and not him, he gets coy: “But you’ll just have to watch it, now, won’t you?”

“How about the times I hitchhiked across the country?” he offers. “You want that story?”

“Gary. This piece is about me and about being in Iowa City, still, and about January and about getting old. It’s not about you. You’re just a backdrop, just a foil, an excuse. This an excuse to write about me.”

Excuses he understands, and they shut him up, for now. He picks up a newspaper, and I commence to staring out the window of Gary Sanders’ latest temporary endeavor: formerly Freshens Yogurt, now temporarily The Best of Books, The Worst of Books. He opened it, he told the papers, because he couldn’t stand to see another business in downtown Iowa City’s pedestrian mail shut down. But all who know Gary know he just wants an excuse to be downtown during the days in winter, and he can’t quite reconcile himself to being a public library catnapper. Besides, he’d have to be quiet in the library. And he’s not a quiet man.

Once, years ago, when we were both in love–me with a greasy masseuse, him with a Hawaiian honey–we danced in the parking lot of the Kirkwood Learning Center where we both worked, and he, wearing shorts with dress shoes and mismatched socks, sang “Love Train” at the top of his lungs.

He puts down his paper and bellows, “On January 21, at 12:30 pm–are you getting this down?–I hereby declare that I, Gary Sanders, am a genius!” He takes off his glasses and heaves a the-world-is-too-much-for-a-man-such-as-I sigh.

“Did you get that down?” he asks.

“On January 21, at 12:32 p.m.,” I read from my notebook, “I hereby declare that Gary Sander’s is a big stupido.”

He considers. “Is that how my obit’s going to read? ‘Gary Sanders. Big Stupido. Dead?”’

“How about this? ‘Gary Sanders. Iowa City rabble-rouser, gadfly, talk-show host, owner of weird bookstore, man of mysterious means, general aggravation, Big Stupido. Dead.'”

He smiles. He likes that. He’s obsessed with New York Times obituaries. He has several of them taped haphazardly on the walls, their headings screaming against a backdrop of cheery white-and-red tiles, posters of yogurt cones and yogurt sundaes topped with cherries and nuts:

“Rupert C. Barneby, 89, Botanical Garden Curator and Expert on Beans, Is Dead.”

“John S. Mollison, Scholar, 87, Rebuilt Lost Greek Warship, Died.”

“AI Gross, Inventor of Gizmos with Potential, Dies at 82.”

“It won’t be long,” he sighs. He’s getting morose; and so I’m glad when a man enters the store carrying an empty watering can in one hand, a stack of flyers in the other. I pick up Mao’s “Little Red Book,” and, in my best Marilyn Monroe imitation, purr, “Reading is so sexy. I just love a man who reads.”

I am middle management for the day. My job is to sell the books. My reward is a piece of Lindts chocolate I spotted in Gary’s “briefcase”–his omnipresent, grease-stained box filled with old newspapers; old political flyers announcing old protests; dirty paper coffee cups; half-wrapped, half-eaten mysterious things.

“Cut it, Amanda,” he says, and pointing to the man with the watering can: “Friend.”

Gary’s friend informs him that tomorrow there will be a rally protesting Bush’s inauguration. The day after tomorrow, a second rally will protest sweatshops. The day after, nuclear energy. Apparently, a few aging white men will be spending all winter on the street comer, freezing, getting angry, holding signs, looking like they are rehearsing for a Midwestern “Monty Python.”

They start talking McGovern. I tune them out and stare out the window at Jim Leach’s office across the way. For the 20 or so years I have called Iowa City my home, I have never, ever seen anybody come in or out of that office. But they’re in there, I know. Behind the drawn shades, I imagine evil things transpiring: deals are being cut with corporate hog-lot owners, ethanol subsidies are being slashed, a man named Abraham is sacrificing his firstborn.

“Weird things are happening over there,” I say after the friend leaves. “Can’t you feel it? The energy, Gary, can’t you just feel it?”

A few years ago, Gary would have played along. His eyes would have gotten wide, his face taken on an exaggerated, conspiratorial grimace. He would have said, “Corporate welfare.”

Me: “Prayer in schools.”

Him: “Jew Bashing!”

Me: “Clitorectamies.”

But he’s grown out of Amanda games. And sometimes the look in his eye lets me know that I should too. My presence seems more often to exhaust than uplift him. Now, mostly he looks at me and shakes his head. “I grow old,” he says, when I try.

Once, years ago, when we were both in love–me with a greasy masseuse, him with a Hawaiian honey–we danced in the parking lot of the Kirkwood Learning Center where we both worked, and he, wearing shorts with dress shoes and mismatched socks, sang “Love Train” at the top of his lungs. We even got the welfare mothers, the high-school dropouts, to join in.

But he’s changed since those years–actually, since he came back from Hawaii with a lei and a frown. Although when summer comes he will inevitably still be loping after fleeing coeds, a mass of papers in hand, a zealot’s look in his eyes; ever since his public-access television show, “Who Wants to Marry a Short, Middle-aged Cranky Guy with No Money?”, failed to fetch him the shiksa of his dreams, he seems for the most part to have given up on love.

These days, Gary, in his middle age, is interested in getting down to business. “Down to business,” he reads from his horoscope. “The time has come to resist temptation and get down to business–are you writing this down? The time has come to resist temptation and get down to business.” He raises his hands in the air and yells, “Halleluiah. Praise the Lord.” I do not shush him, because his preacher’s voice is preferable to some of his others. Down to business. The phrase runs through my head, and all and all, it doesn’t sound too bad. Preferable to what most of us in this tiny dot of a town in the center of the country have been doing. Preferable to staring out at a gray January day waiting to catch a glimpse of a real-life Iowa City Republican. Suddenly, a fourth-grade teacher is in my head, and she’s telling me to “Take the bull by the horns,” and that ”Today is the first day of the rest of your life.” “Wake up and smell the coffee,” she says. Another voice, this time with a jeer, says, “Shit or get off the pot.”

My body begins to vibrate, my legs want to move. I want things–something, anything–to happen. I want to sell a book.

“Enough of this!” I say. I pick up a copy of Dennis Rodman’s Bad as I Want to Be, jump on the ledge and thrust my hip out in a model’s pose. When a group of boys walk by, I mouth, “Uh, ah, reading is soooo sexy.” One of them stops, stares and mouths back with real concern, “Is something wrong? Do you need help?”

“Good job,” Gary says.

“Gary!” I jump off the ledge and run my hands frantically through my hair. “Why don’t we create a marketing plan, get a small-business loan, apply for one of those tax-relief thingamajigs. We could actually do something. We could make a go of this.”

I’m having a vision. It’s the bookstore/coffeehouse of my dreams. I see plush couches and leather binding. I see a place where people actually converse. I see poets talking iambs with politicians. I see career criminals and starving artists embracing. I see myself having a scintillating conversation about French literature with a mysterious man.

“Upper management will consider your ideas,” Gary says. “But in the meantime, why doesn’t middle management begin by organizing the books?”

I look around at the 300 or so ratty books arranged in no discernable order–What to Expect When You’re Expecting next to Great Expectations. Danielle Steel next to Dante. Wally Lamb next to Charles Lamb. A wave of exhaustion runs through me. I sit down and resume staring out the window, this time at Hawkeye World Travel, from which perky, tanning-boothed blondes bounce in and out constantly. I look at the recently deceased and papered Treasures knickknack store. It’s sad when a store with such a blithe name goes under, even though I always felt sympathy for the farmers’ wives who’d stumble upon the store–while doing Christmas shopping, say, or before the Iowa/Iowa State Game–scratch their heads and say under their breath, “Don’t people have better things to do with their money?” “Gold-plated roses? Giraffe-shaped coffee mugs? Elephant snout vases?” “That’s different,” they’d say, as they handled a bronze com cob infused with a grenade pin.

But that, of course, has always been one of the things that separates Iowa City from its state. We are different. We are the types of people who buy such things, and we are proud of it. And we–the best and the worst of us–are the types of people to always buy books.

Or maybe not any more. The ped mall’s awfully empty these days. Maybe now we’re buying our picture frames at Target, ordering our books online. I’ve been here for two hours, and the only people who have entered looking for anything other than yogurt are Gary’s friends. And either they’ve given up on books because they read somewhere years ago that literature is dead (they’ll tell you so with a knowing look, a touch of feigned sorrow in the shrug of the shoulders), or it’s their books that Gary’s peddling.

Partly because she’s pretty, partly because he’s incapable of reserve, it’s too much for him. He stands up suddenly, knocking over a chair, and on his way toward her trips over a table. He’s coming at her, arms pinwheeling, head in a matador position. She takes a few quick steps back with a horrified look on her face.

We are also within spitting distance of the anti-fountain fountain. There’s something vaguely depressing about that fountain, even in the summer. The way the water refuses to return into the holes, and instead clops on the marble like a herd of horses, making bricks slick, causing children to fall and cry, adults to yell over the noise, and the guy strumming some awful rendition of “Sugar Magnolia” to strum even louder. But in the summer, despite all the cacophony, there’s still that air that glides across the skin like a silk shirt, there’s the deep shadows and the Disney-blue sky and the whiff, occasionally, of earth; the smell that reminds us that this world is being nourished by the land around us, and that despite Steve Atkins or R.J. WinkIehake, good things are happening here.

But in the winter, everything feels doomed in that Greek tragedy kind of way, when an infraction against the gods (the killing of Eric Shaw) ensures that all the money and energy and good intentions in the world will not bring about a workable fountain, kiosks with telephones and newspapers, or keep Iowa City–the treasure of Iowa–from dying.

Or maybe it’s just me. Maybe it’s the frostbitten January sky, the post-holiday blues, the dirty snow and the sallow complexions. Or maybe it’s the fact that once you reach a certain age–mid-30s apparently–optimism takes a certain kind of energy that belongs to the perky blondes who, on the first day of the semester, are already planning spring break in Cancun at Hawkeye World Travel.

A college-aged woman enters. “A customer!” I whisper to Gary.

“A customer!” He repeats. “A real one!”

She browses. Gary and I sit, very silently, for a while.

“Stay cool, Gary. Just keep it cool.”

Partly because she’s pretty, partly because he’s incapable of reserve, it’s too much for him. He stands up suddenly, knocking over a chair, and on his way toward her trips over a table. He’s coming at her, arms pinwheeling, head in a matador position. She takes a few quick steps back with a horrified look on her face.

“Hello!” he bellows, after he rights himself. “My name is Gary Sanders, and she … ” he says pointing to me, “is my middle manager, Amanda Coyne. Let us know if we can help you.”

She continues to browse. He moves toward her. She moves away.

“If there’s anything at all we can do for you…”

“I’m just looking,” she says and picks up a copy of Ann Tyler’s Ladder of Years.”

“How much?” she asks.

Gary leafs through the book. “Let me see,” he says. “A hard copy? Published recently? Let…me…see…” he places one finger on the side of his temple and taps. “So, what do you do.”

“Five dollars,” I tell the girl. She reaches into her backpack for her wallet.

“Hold on,” he says. “Just one second. Her wallet goes back into her backpack.

“She,” he says, pointing to me, “is just middle management. Just hold it right there. These are difficult times. Middle management be running around giving product away. For you though, today and only today, I’ll sell you this fine book for 218 dollar and 30 cent.” Now he’s stumbled into some kind of mutant ped-mall slacker voice. “218 dollar and 30 cent.” The girl chuckles nervously. She begins to slide toward the door.

“Now seriously. You look like a nice young lady. What is it you say you do?” She’s getting scared. She’s halfway out the door. “Seven dollars,” he yells at her back. “Seven dollars is my final offer. Take it or leave it. Today and today only.” She escapes.

*

‘Tm depressed, Gary,” I say. ”I’ll never get out of this town. Nothing will ever happen and I will never leave. I’ll be stuck here, with you, forever. Can I have that chocolate, please?”

”You sell a book, you get the reward,” he answers. “Has anyone ever told you, by the by, you be one high-maintenance girl? You be all the time need some attention.” This is punctuated with a homeboy pointing of the finger; a downward movement of the arm; a short, intellectual, radical leftist imitating Dr. Dre.

But that’s not his worst. His worst is his hillbilly impersonation. And this he commences with a whooping, “Hey Bubba,” when Larry Baker, Iowa City’s number-one Southern-writer boy enters. Let me rephrase that. Larry Baker does not just come in, he struts in, in the way that a New York TImes best-selling author struts. Or maybe I’m projecting. Maybe I’m just imagining myself walking into a little used bookstore after such a success.

Introductions are made, and I–just like any other wanna-be writer in this town–pretend to only have vaguely heard of him and his book. He tries to talk to me, but I answer in monosyllables and become interested in the life of Malcolm X.

This might be the only town in the world where nobody will like you if you become a famous writer.

They start talking McGovern. I stretch and yawn and think deep thoughts. I think about how downtown Iowa City is doomed: how it will never get a Gap or J Crew or Ann Taylor. I think about no matter how many times it changes ownership, loud, bad muzak will always blare out of the old Holiday Inn’s loudspeakers. I think that no matter the money I spend at Dombies, I will never look like one of the girls who work there. I think about how the Englert will inevitably become a sports bar, and about how those of us who don’t frequent such places will forever spend our days caffeinated and frustrated at the Java House of sexual repression.

I am brought back by Gary yelping, “Ya’ll come back now, you hear?” at Baker’s back.

During my reverie, someone has added black streaks of charcoal to the dusky sky and cranked this spot on the earth a notch away from the sun.

The mercury’s dropping, fast. Tonight it’s going to be a cold one. The wind’s gotten louder and has taken on the cry of a lonesome child. Later, it will become a madwoman’s screech. Everywhere, blinds are being drawn, furnaces are kicking in, bundled children are walking away, fast, from school. College students are wondering why they didn’t choose a university down south. Farmer are cursing their forefathers for not making it farther west. Halos of light surround lampposts, storefront windows are fogging, and everybody, including Gary and me, is heading home.

Gary adds more old newspapers to his briefcase, wraps up his half-eaten sandwich and turns off the lights. We stand outside the shop for a moment. He is wearing his pile cap and a down coat that reaches his feet. His glasses are spotted and fogged, and his gloves don’t match. I have a nearly overwhelming desire–archetypal almost–felt by hundreds of Iowa City women since that fateful day in 1977 when he disembarked off a Greyhound bus–to hoist him over my shoulder, take him home, feed him and clean him up.

I start singing: “Gary, Gary Sanders, King of the Iowa City ped mall.”

“There you go,” I say, “Gary, there’s your obit ”

“Cheer up,” he says. ”This place ain’t so bad. Besides, spring’s right around the comer.”

We part ways and walk toward the warmth. Toward home. He is humming his obit. I have a hand in my pocket, fingering my stolen piece of Lindt’s chocolate.

Amanda has an MFA from the University of Iowa in creative writing. For many years she reported from Alaska, covering everything from crime, to the arts, to the outdoors. She’s been a stringer for Bloomberg, The New York Times, and a contributor to Newsweek. She’s been published in many other publications, including Harper’s and The New York Times Magazine.