By Chris King

Originally posted April 2014 at Confluence City

I have a favorite Anne Tkach memory.

The setting: Fred Frictions’s kitchen, adjacent to Frederick’s Music Lounge in its heyday. The time: somewhere in the middle of the afterparty that never ended while Fred Jr. was running the Lounge. We were drinking, smoking, and passing the guitar, naturally. I know Roy Kasten was there, because we locked eyes in joyous amazement when the simple chords Anne was strumming turned into a song that Roy wrote with Michael Friedman, “Everything You Love Will Be Carried Away.”

Joy and amazement: not uncommon experiences, when Anne Tkach was playing music.

The specialness of this particular musical experience requires a little explanation, since most people, unfortunately, don’t know who Michael Friedman is or the kinds of songs he writes.

Roy and I went to graduate school in literature at Washington University with Michael. He was an obsessive fan of poetry and songwriting who suddenly started writing songs, frequently with Roy’s assistance on guitar. The typical Michael Friedman song is very long, intensely personal, allusive in complex ways, and for those reasons difficult to learn and to sing.

There was a time when Roy and I were the only fans of Michael’s songs. Anne and other musicians began to hear his songs through the Guitar Circle, a song-swap that we started at Michael’s instigation when he still lived in St. Louis and wanted to encourage his little brother, who was passing through town at a tough time, to focus on his own songwriting.

Through the Guitar Circle, some of Michael’s favorite musicians and songwriters – Anne, Fred, Bob Reuter, Mark Stephens, Sunyatta, Adam Reichman, John Wendland – became fans of his songwriting. Roy drew upon this incredibly deep pool of talent when he produced two records for Michael, “Stories I Have Stolen” and “Cool of the Coming Dark.” Anne played bass on three songs on “Cool of the Coming Dark,” including “Everything You Love Will Be Carried Away.”

She played those bass lines as tastefully as can be imagined, though they were anything but hard for her (or anyone) to learn. Like many of the best singer-songwriters, Michael and Roy go in for the three-chord, two-part songs. But learning a Michael Friedman lyric poses a real challenge for anyone. “Everything You Love” has five long stanzas with absolutely no predictable rhymes or familiar lines, unless you happen to have read every book and heard every record in Michael’s extensive collections.

As Anne broke into the first verse – it’s about Bob Dylan accepting an Oscar on TV, though typically for a Michael Friedman lyric, Dylan is only alluded to, never named – sitting around Fred’s kitchen table, I could see that Roy had no idea she had been learning their song on anything other than bass. It is, needless to say, the highest tribute a musician can pay to a songwriter, to learn one of their songs. Anne was a musician we admired as much as any musician in town, on Earth. It was an unforgettable tribute.

Anne eventually recorded her version of their song with her band Rough Shop on their record “Far Past the Outskirts,” which I only heard after I learned that Anne had died in a house fire. Anne played in a lot of bands, a lot of really great bands, and they released a lot of records, a lot of really great records. When I started sorting through my collection for records Anne played on, to deal with my grief, I found about 10, and I’m sure that’s less than half of her recorded output. Even these 10 records – with the bands Nadine, Bad Folk, Peck of Dirt, Michael Friedman, Ransom Note, Rough Shop and Magic City – would make for a musical career that would make anyone proud.

And that is even with a career, with a life, cut tragically short, when Anne was at the height of her creative powers as a musician and just starting to emerge fully as a songwriter and a singer. I am in awe at her accomplishment, and unspeakably saddened at her sudden loss.

I have a few more personal thoughts about Anne.

She was an incredibly supportive friend. Anne must have attended every event our arts organization Poetry Scores produced. I have many memories of her strolling into an event – in recent years, accompanied by the love of her life, Adam Hesed – and making an effort to connect with everyone before she moved onto the next friend’s gig. Our events are collaborative, so she could have been supporting any of a dozen friends, or all of us. Hundreds of St. Louis artists would say that Anne was there for them, again and again.

I must say she also handles a band break-up as skillfully as I can imagine that being done. She briefly played in a version of my band, Three Fried Men, after Robert Goetz invited her in on drums (another instrument she mastered). As dozens of musicians would tell you, she was a pleasure to play with, learning songs without apparent effort, knowing what to play without being told, having fun in the process. Robert and I had a falling out after only a few band rehearsals, unfortunately, and I lost Anne in the split. I don’t remember how she told me she’d rather play music with Robert than with me – my memory sparing my ego, perhaps – but I do remember it left no bad taste whatsoever. My friendship with Anne continued without a hiccup.

I am very relieved to say Robert and I later patched things up, and he was the next person, after Roy, whom I called when I heard that Anne was gone. I needed to speak to someone with whom I had shared, however briefly, the experience of playing music with the one and only, the irreplaceable and unforgettable, the immortal Anne Tkach.

Anne’s friends have been seeing a lot of each other since she died. A series of events in the local music and arts scene became tributes to Anne – wakes, in a way – in the week and weekend after we lost her. The way we lost her, in a house fire apparently sparked by a lightning strike, left us all numb and perplexed. The fact that she was sleeping in that house to care for her ill father only made the loss more deeply unjust and inexplicable. We have all been talking about that.

I was talking about that with Robin Allen, a fellow musician, at Dana Smith’s art show on Friday. Dana is also a musician whose band Cloister gigged with Anne’s bands. Everybody at the art show was grieving. I talked to Robin about how the whole lightning storm thing was making it harder for me to grasp her death and come to terms with it.

“In a way,” Robin said, “the way she died, it’s like we all got struck by lightning.”

We were also talking about that the night before, the night of the day we all heard the tragic news. We were drinking and waking Anne at Ryder’s, the bar owned by the love of her life, Adam. The same violent storm system that apparently killed Anne was still blowing through St. Louis. I was sitting near the front door with Robert Goetz, Gina Alvarez and Kevin Belford.

The storm kept blowing the door of the tavern open, and then closed again. Since the door was also being opened and closed by people coming into the tavern, it was a little weird whenever the door opened and closed, but nothing came into the tavern but a little bit of the storm.

I decided that Anne was a part of the storm now, and that Anne kept coming into the tavern, connecting with her friends, and then moving onto another friend’s gig. Whenever a lightning storm comes to St. Louis now, I will think of Anne coming to see us. Whenever I hear her music or see lightning in the St. Louis sky, I will think of Anne Tkach.

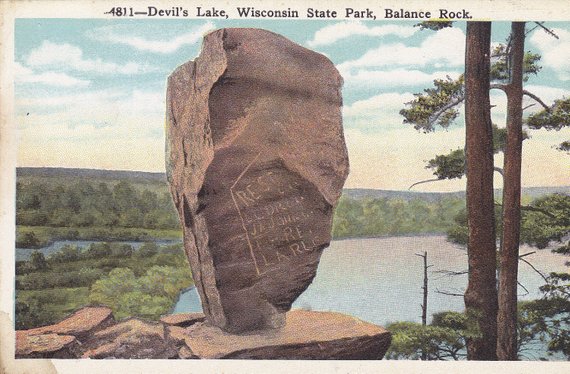

I’m pursuing the end of the world petroglyph idea and as part of a working trip to Wisconsin visited the only publicly accessible ones in the state. I had just read an essay in The Believer about young college men being drowned in some kind of smiley face cult conspiracy and then right before I came upon the glyphs there appeared a really frightening piece of smiley face graffiti. Lucky I’m too old to be caught up in the Zeitgeist!

I’m pursuing the end of the world petroglyph idea and as part of a working trip to Wisconsin visited the only publicly accessible ones in the state. I had just read an essay in The Believer about young college men being drowned in some kind of smiley face cult conspiracy and then right before I came upon the glyphs there appeared a really frightening piece of smiley face graffiti. Lucky I’m too old to be caught up in the Zeitgeist!